One of the highlights of my tenure at RED Academy was developing the Community Partner Program.

After going above and beyond my role as a teacher assistant, RED brought me in full time to help grow the company. When I joined RED Academy it was entering its third cohort of full-time students. It was a new technology school that was trying to do “bootcamp” better. Longer programs containing several client projects was the key selling point. For the UX professional program, there were two client projects. And a portfolio project with the development students. (The programs are different now — if you’re curious click here.)

I was also a student of their very first cohort. I may have noticed the challenges with the first cohort of community partners. There was uncertainty about their involvement. There were community partners dropping out last minute. The instructors were still able to deliver, but it was stressful. RED needed to create a process, the materials, and find projects to fulfill it’s growing needs. And this was to be my piece to figure out and build.

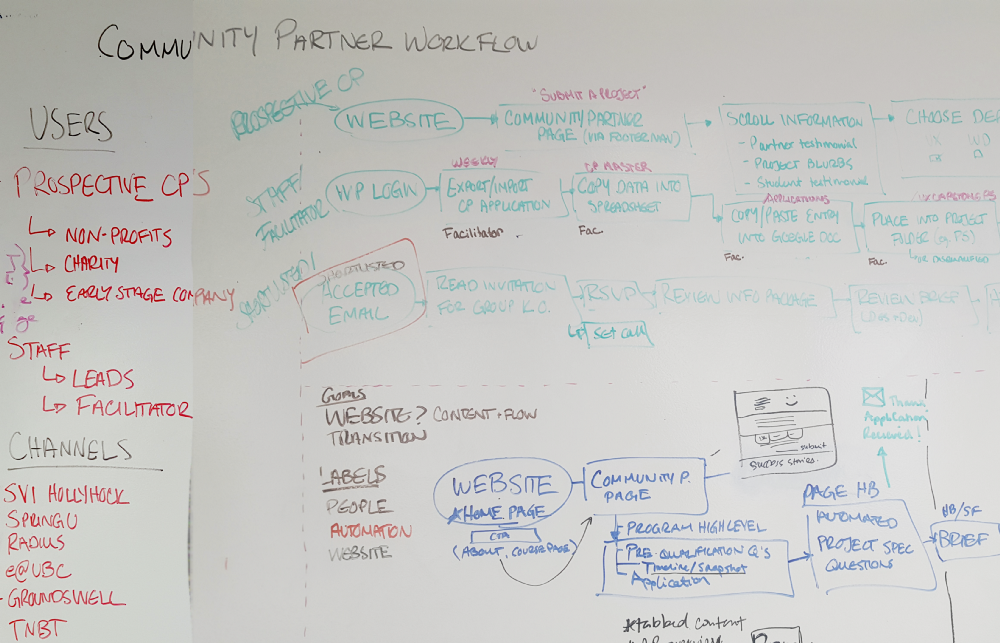

I observed the process of a full cohort of student projects to uncover the different scenarios and needs of the program.

RED wanted to simulate an agency environment as much as possible. Projects would start in the UX design program then hand-off to the development program, and eventually into the digital marketing program. At the time, programs had different objectives and criteria for the project. And potential partners had different needs — often outside of the scope of students abilities.

The first version of the application form included some fairly technical questions. We had many, “I don’t know how to answer this” responses. For those that were answered, they were often inadequate. Instructors and I had hours of follow-up with community partners to work out each project.

An application form would have to consider each of these variables and ask questions in a way that would help clarify the project. And for around 50 projects every 3 months, it became evident we needed to automate.

What happens when the client doesn’t want to go with the design the students produced? Or if the development is incomplete? What if the partner drops out last minute, or doesn’t return calls or emails? These questions all needed an answer because we were experiencing them, and expectations were high all around.

We needed a policy and a way of packaging it to achieve accountability from all actors.

The goal of the design was to:

I completed research with a sample of Community Partners and staff-our two main users of the system. I conducted user interviews with both groups to capture their experience, expectations and desires. I conducted contextual inquiries with the staff to see how they used our folder systems and files. Although I had an idea of what the problems were, I wanted to ensure that I didn’t miss anything and that users felt engaged in the system.

Questions were not easy for people with non-technical backgrounds to answer. They were also inadequate to capture all the information critical to determining a project’s eligibility. My process was to work backwards. I worked with the lead instructors to uncover learning objectives, environments, and criteria for the projects. We asked questions that would screen for the criteria. Then we worked to translate those questions into non-technical questions. In the example below, we predicted that partners would know about their analytics more than the data behind the analytics. And if they didn’t have analytics, we thought it would be sufficient for them to guess.

To address the inefficiencies in the selection process between instructor teams, we created a metric system to evaluate projects. As mentioned before, each instructor had different criteria for what made a good project. Without an evaluation system, selection discussions often went into hypotheticals and compromise was challenging. With a metric system, each team would submit their own score, and projects with the overall highest score would be selected.

We also investigated our technology options. RED had adopted HubSpot Sales and Marketing for marketing automation, however, didn’t use the “Sales Dashboard”. I could use it to serve as a CRM and automate some of the communication. We would also adopt the system to facilitate our application process. We used the HubSpot landing pages for applications. With HubSpot landing pages, each project could have its own set of questions and respective action workflows. Now applicants could receive immediate feedback and all other correspondence in a timely manner.

Everything was ready to launch. We had HubSpot pages, communications, contracts, evaluation processes, and documentation to hold it all together. There was one challenge not addressed, filling the pipeline with a steady stream of projects. In the background, the organization started to re-structure in order to trim resources. In the re-shuffling and re-distribution of resources, my role as the Community Manager was cut. I had successfully automated myself out of a job, a goal I was trying to reach. But this meant there would be no one would be sourcing partners.

I had earlier investigated an alternative off-the-shelf solution, Riipen. Riipen was a local start-up that manages project-based learning for educational institutions. They were confident in their ability to source the large number of projects needed every quarter. For now, it seemed like the best option to make sure the burden of sourcing didn’t fall on instructors. This meant that all the work I did to build our own system was going to be shelved for the time being.

Using the human-centred design process to re-design our program ensured that we saw our service from the lens of both users; prospective and current Community Partners, and the instructor staff who had to evaluate and manage projects in the classroom. Although unable to thoroughly test solutions before my departure, the research, planning and design into the system allowed me to expand my experience to designing for services and programs.